Carole Levine July 18, 2021

Times are tough. There’s nothing new in that statement and certainly the events of the last few years – the COVID-19 pandemic, racial unrest, and economic downturn – have exacerbated the plight of many of those whose very lives tottered on the edge of bare subsistence and homelessness. The reality is that it is worse than you think. For all of our shouting about raising the minimum wage and “Fight for $15,” the federal minimum wage remains at $ 7.25 an hour. And study after study shows that one cannot live, especially if one is supporting more than just oneself, on a salary of $15.00 per hour. A recently released annual study from the National Low Income Housing Coalition “Out of Reach” finds that people working at minimum wage jobs, full-time, cannot afford a two-bedroom apartment in any state in the country, or even a modest one-bedroom apartment in 93% of the U.S. counties. This is based on affordability defined by that worker spending no more than 30% of his/her income on rent.

Of course, this does not mean that all of the working poor (and this nation has a lot of working poor who earn less than $15.00 per hour) are out on the streets. What it does mean is that they are paying much more than 30% of their salary to cover housing, leaving them with less for food, health care, utilities, transportation, clothing, schooling (if they or their children are students), travel, or even the occasional gift or extravagance like a meal at a fast food restaurant. It means that in this nation of wealth and abundance we have people who are struggling to keep the most basic of basics – a roof over their heads – and we are pushing the government to raise the minimum wage to a level that still will not support that need. How can this be? And what does this mean?

Let’s start with wages and the growth in salaries for workers. Those who are at the bottom of the scale of hourly paid workers, gained the least in terms of salary growth, according to the 2021 Out of Reach report. Citing multiple surveys and reports, Out of Reach indicates that between 1979 and 2019 inflation-adjusted hourly wages grew at just 6.5% for the lowest wage workers and 8.8% for medium-wage workers. For some Black and Latinx male workers inflation adjusted wages actually fell during this period. Contrast this with the highest-paid workers whose wages grew by 41.3%. During this same period productivity grew by nearly 70% while compensation for production and supervisory staff grew by just 12%. It should come as no surprise that this period saw growth in the numbers of “working poor” in this nation, numbering seven million in 2018 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It is possible that this number could be even higher. Out of Reach also cites the racial disparities within the likely population of the working poor: 7.2% of Black workers in the labor force for at least 27 weeks per year were working poor, compared to 7% of Latino workers, 3.5% of white workers, and 2.3% of Asian workers.

One factor that has impacted the pervasiveness of low-wage jobs is the lack of support for organized labor and the slowing growth of unions. This has likely directly affected the bargaining power of low-wage workers. Unions have helped to raise wages for low-income workers, especially Black and Latinx, historically. But unionized worker fell from 27% in 1979 to 11.6% in 2019. There is no question that this has had an impact on wages for workers at the lowest end of the scale, making it harder to pay the rent.

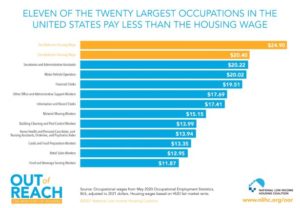

What will it take to afford decent housing? According to this report, to afford decent a one-bedroom apartment that will only take 30% of one’s hourly salary, a worker would need to be paid $20.40 per hour. For a two-bedroom apartment, a worker would need a salary of $24.90 per hour. Eleven of the twenty largest occupations in the United States do not meet this cut in terms of what they pay their workers. Workers in these occupations account for more than 36% of the U.S. workforce, excluding farmworkers. If we just take retail sales or food and beverage service, we are looking at nearly 14 million full-time workers who cannot afford the rent. Home health aides, personal care workers and nursing assistants (jobs that are predominantly Black and Latinx) earn wages that are 2/3rd of what is needed for housing.

It is important to understand that Blacks and Latinx households are harmed the most by this unaffordable rental market. Why? Because they are most likely to be renters at all income levels. According to the 2020 Census, in 2019 28% of white households were renters. Compare that to 58% of Black households and 54% of Latinx households. The racial wealth gap as well as ongoing discrimination in opportunities for homeownership for people of color adds to the numbers of renters of color. These low-income renters are also the ones who have been most impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of their employment as well as their health and wellbeing. Native Americans were also hard hit by the pandemic leaving them with similar issues of economic insecurity around work, rent and health. All of these groups continue to face slower recovery as the nation begins to move forward. Their confidence in their ability to meet their current rent, even as we recover from the pandemic, remains limited and their need for assistance in this area in order to stay housed remains an issue.

There is no good time for low-income renters to find affordable housing. It does not seem to make much difference in the housing market if we are in a down time or a time of economic growth. Before the pandemic there were only 37 affordable rental homes for every 100 renters with low-incomes across the country. As a result, 85% of low-income renters could not afford their rent and 70% were paying more than half of their income for housing.

When the economy is good and growing, the building industry focuses on housing for high-income renters who can bring them the greatest profits. The median asking rent for apartments in multi-family buildings, built in 2018 and 2019 was $1,620 per month. This is out-of-reach for low-income renters. Only 32% of all renters in 2019 could afford this level of rent. Clearly, there is a disconnect between the need for housing and what is being constructed. But is there a way to address this disconnect?

According to Out of Reach the answer lies partly in the enactment of federal policies some of which already exist and just need to be supported and expanded. Others need to be developed. Here’s what is being suggested:

- Expand Rental Assistance. Congress did this during the pandemic with the Emergency Rental Assistance Program that was part of the American Rescue Plan. Now, Congress needs to expand this with the Housing Choice Voucher Program which would provide vouchers that would cover rent beyond the 30% of a low-income earner’s salary so that there would be no debt or reach for that person beyond 30%. Two proposals are out there related to this: the “Family Stability and Opportunity Vouchers Act” that would create 500,000 new housing vouchers and counseling services for families, and the “Ending Homelessness Act” that would fully fund the Housing Choice Voucher program so it could assist all income-eligible families.

- Expand the Affordable Housing Supply. The federal government needs to invest at least $45 billion into the national Housing Trust Fund (HTF) to create, preserve or rehabilitate homes for renters with very low incomes. At least 90% of these funds are used for rental housing and 75% of that served those with extremely low incomes. Public housing is in dire need of funding for rehab and repair and is a critical part of the infrastructure of this nation. The backlog of repair costs totals $70 billion (NLIHC, 2021a). Some funds ($40 billion) are included in the American Jobs Plan but other bills (going back to the 116th Congress) are also out there to cover these costs.

- Create a National Housing Stabilization Fund. This would be the emergency assistance that would have been so helpful to so many low-income renters during the pandemic. When you have limited resources to begin with and suddenly experience a shock to your finances (such as losing your job), this is what was needed. This kind of “Eviction Crisis Act” that was introduced in the 116th Congress would create a fund for state and local government use to provide short-term financial assistance and housing stabilization services.

- Provide and Enforce Renter Protection. Most voucher holders have a hard time finding landlords that will accept their vouchers and this kind of discrimination around “source of income” for renters needs federal protections. The “Fair Housing Improvement Act” that was introduced in the 116th Congress would prohibit such discrimination based on sources of income. Enforcing the existing protections in the Act would reduce racial and ethnic discrimination as well as that based on sexual orientation, gender identity or marital status. Other bills on these issues are also pending. Having a lawyer when a low-income renter faces eviction is a rarity, but when they do, they fare much better in court. This also needs some federal attention and Congressional oversight. A national right to counsel and funding to make it happen is very much needed.

Going back to the laws that existed prior to the pandemic will not make things better for low-income renters. More than likely, that scenario will make things worse. Knowing this should make us all uncomfortable. It is unconscionable that those who make the lease should have to pay a larger and larger portion of their income to keep a roof over their head and then have to weigh the value of all other needs against paying the rent. The answers in the federal actions suggested by the Out of Reach report all have merit, but the chances of gaining traction in this partisan Congress make their passage seem dim. Perhaps there are other ways.

Many have been working for years to raise the minimum wage. The Fight for $15 movement has made great strides in moving the needle in some cities, communities, and states to change what the base salary is for workers. What this report says, however, is that even $15 per hour is not enough. We need to be lobbying and approaching employers for a “living housing wage” of $20.40 per hour (for a one-bedroom apartment) or $24.90 per hour (for a family needing more)! No one should stop pushing to change the minimum wage to $15 per hour, but at the same time that should only be seen as a starting place.

If we are to truly move beyond the racism and classism of what it means to be a low-income worker and a low-income renter, we need more than federal government policies. We need employers that see workers as their partners and unions as their allies. We need landlords who see tenants as valuable, whatever their income sources are, and we need to see elected officials who value all of their constituents equally. There is great value and wisdom to be found in this report. Let’s hope we can use it to make things better for everyone.