Marty Levine

05/19/2021

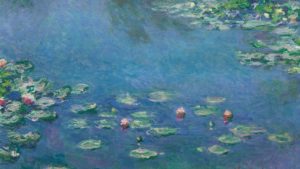

Earlier this week, feeling the freedom that being fully vaccinated against COVID has brought it was time to enter the halls of the Chicago Art Institute for the first time in more than a year. Wanted to view the “Monet and Chicago” exhibit.

The paintings were glorious, yet I left the museum disturbed by how the exhibit’s narrative glossed over, as we too often do, the important but uncomfortable context that allowed Chicago, its famed Art Institute, and Monet to have a special relationship.

The paintings, filling several large galleries, provide a comprehensive view of the artist’s life and work. They also tell another story, one of the relationships of wealth and privilege to what is seen as our national cultural heritage. Before you can view a painting, the museum glorifies the men and women who established a unique relationship with a French master who never crossed the Atlantic or visited the city.

The museum had missed the moment to present these men and women with a more nuanced sense of their lives and the times they lived in. It was a missed opportunity to allow us to consider the difficult and complex history of nobles oblige, excess wealth, privilege, and human suffering.

The story as the museum tells it, sees our ability to enjoy the wonder of Monet’s genius as a wonderful gift from three prominent and civic-minded families. “In 1891, Bertha and Potter Palmer acquired some 20 paintings by Monet—including several from the Stacks of Wheat series—a fraction of the 90 canvases they would come to own. That year, Martin A. Ryerson, who served as a trustee and eventual vice-president of the Art Institute, bought his first of many paintings by the artist…. the museum’s collection grew thanks to generous gifts…Annie Swann Coburn…”

Walking the exhibit halls that message is quite clear, recognized over and over again. We are all beneficiaries of the willingness of these special men and women to share their privilege with us. This is the story of American philanthropy that we are used to hearing. Those of us who can enjoy an afternoon amidst the painter’s haystacks and water lilies should be grateful for gifts we have been given and honor those who made these gifts.

Missing entirely is a fuller sense of the human context that allowed these three families and their contemporaries who profited during our nation’s first gilded age to live their lavish lifestyles, dabble in the arts, and be seen as pillars of their community. Missing is the story of the human pain and suffering that was Chicago of their time.

Chicago, around the turn of the 20th century, was a rapidly growing city, fueled by the nation’s emergence into the industrial age. For some, the extremely fortunate few, this was a time when it was possible to become fabulously wealthy. Potter Palmer was there for the beginning of modern retailing, starting a firm that later blossomed as Marshall Fields, and who helped create a burgeoning hospitality industry when he built the still operating Palmer House. Martin Ryerson grew his parents’ wealth by developing the largest lumber business in the midwest. Annie Swann Coburn’s husband had earned their wealth as a prominent patent attorney.

But there is more we should know about the community that they profited from.

Daniel Hautzinger described it for WTTW when he wrote a few years ago that their Chicago “of all American cities…is perhaps the most vivid example of the Gilded Age in all its glory and squalor. It experienced unbelievable growth through the period: in 1870 its population was just under 300,000; three decades later it was almost 1.7 million, making it one of the five largest cities in the world just 60 years after its founding. As the city was rebuilt after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, it became the birthplace of the skyscraper and a hotbed of innovative architecture, and in 1893 Chicago established itself as an important global city with the celebrated World’s Columbian Exposition. But it also epitomized the social problems of the time. Much of that huge population surge was made up of poor European immigrants who lived in overcrowded slums on the West and South Sides, doing grueling work for low wages in the city’s stockyards, factories, and on the railroads.”

These working men and women lived a different life than the Palmers, the Ryerson, and Coburns. Historian Alan Cornwell described gives us a picture of those too often ignored lives writing that “the Chicago meatpacking industry, along with other industries, began to expand and grow. There was money to be made both at home, as well as overseas. Making profits initially relied upon two major things – – cheap labor, and the absence of any type of regulation…families were forced to live on a family wage. Sometimes, children worked as long as their parents, usually 10 to 15 hours a day. Their living accommodations were essentially an extension of the hell that they endured during the day.”

Upton Sinclair, in “The Jungle” published in 1906, captured the pain of this workers’ reality through one man’s experience. “In the beginning he had been fresh and strong, and he had gotten a job that first day, but now he was second-hand, a damaged article, so to speak, and they did not want him. They had worn him out, with their speedin-up and their carelessness, and now they had thrown him away!”

No time or cash for that worker and tens of thousands of others to think about collecting fine art.

These were also the years in which Chicago built its racist infrastructure. As described by Rhonda Nara Edwards, “As a result of the Great Migration, from 1890-1910 the African-American population of Chicago increased from 15k to 40k. By 1917, the Chicago Real Estate Board began setting up the Chicago Black Belt. The Chicago Real Estate Board is on record stating “Inasmuch as more territory must be provided (for Negroes), it is desired in the interest of all, that each block shall be filled solidly, and that further expansion shall be confined to contiguous blocks with the present method of obtaining a single building in scattered blocks discontinued.” These patterns formed the foundation for the redlining practices that have kept black Chicago trapped, isolated, and deprived of the economic benefits that their white neighbors were able to access.

The Chicago’s Art Institute chose the story behind its relationship with the art of Monet with a narrow lens. They chose the parts of the story they would not tell. In doing so they are continuing the mythology of individual greatness. And in doing so they are ignoring the painful truth that we have learned white privilege. They need to do better.

Your article helped me a lot. what do you think? I want to share your article to my website: gate io

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.