Marty Levine

June 20, 2022

Years ago, I met the Israeli author A. B. Yehoshua in a Haifa University classroom looking out over the blue waters of the Mediterranean Sea. He was proud and confident. With all of its imperfections, Israel was the Jewish Homeland, and only there, he said, could you be a “full Jew.” Only there was it possible to live every part of one’s life “Jewishly” and only there did you not have to separate your identities in two, Jewish and secular. Those of us living outside Israel were “half-Jews.” he said.

I had entered that room already ambivalent about Israel and its connection to me as a Jew. But shortly after returning from that trip, I wrote “As a son of immigrants who found in this country a haven from the difficulties of Eastern Europe at the turn of the 20th century, I grew up in the rhythms of the Jewish calendar intermixed with the tempo American time – our holy days and our holidays. The smells of our Jewish kitchen and the taste of pizza from the corner shop described a wide range of food and tastes. Religious school and junior congregation mixed with baseball practice to fill up my days… Israel is not a perfect country, a perfect government or a perfect society. It is, however, the one place where every aspect of life on a societal, communal, and individual level can be lived as an expression of Jewish Values! ”

When I heard the news that Yehoshua had died I went back to that day on that hillside looking out over that sea. I thought about how that moment had stuck with me, but also about how much had changed since then. The Israel that had seemed a noble work in progress, had become something else. The decades of the occupation had been toxic. It was not a land that embodied Jewish values.

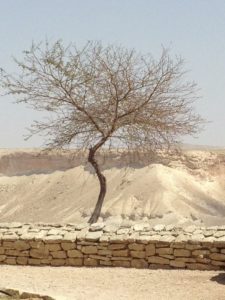

I traveled back to Israel frequently after that day. I’ve never lost my sense of awe for the land. The beauty of the desert and the ocean mixes with the sense that wherever you walk there is another piece of human history to be discovered, always leaves me with something new to discover and to learn. With each leaving there was always a desire to return.

But with each trip, the reality grew that there was a dark side that could not be ignored. The omnipresence of guns and soldiers. The walls that separated farmers from the fields. Checkpoints and separate roads. The palpable difference between ”Jewish Jerusalem” and “Palestinian Jerusalem.” The stories of our Jewish Israeli friends whose relationships with their once Palestinian friends had irreparably changed. The blotting out of a Palestinian reality. It has become a country I no longer feel welcome in, which no longer feels like a place that seems to be aligned with my understanding of what Judaism demands of us. And so, I no longer travel there, it has become a place of pain and sorrow.

But I was not alone in this transition. A. B. Yehoshua, who had challenged me decades ago, also struggled to reconcile his passion for a mythical Israel with the reality it had become. In his later years, he recognized the failure of his nation, the place that he loved dearly, to fulfill his vision. He now saw the years of the occupation had made his hope for a “two-state solution” an unrealistic phantasy; he saw that his dream of a Jewish state living alongside a Palestinian nation was not possible. He began to advocate for the creation of a bi-national state as the only way to protect his Jewish persona, that he could be a “whole Jew” even in a land that was not just a Jewish state.

In 2018 he wrote about how the searing reality that Israel is had eroded his faith in its future. “Yet, just when the term ‘Palestinian state’ is becoming a staple fixture in the international sphere, I and some of my good friends who fought for it for 50 years feel – and I hope I am proved wrong – that this vision is no longer viable in practice. Indeed, it has become only a deceptive and crafty cover for a slow but ever-deepening slide into a condition of vicious occupation and legal and social apartheid with which we in the peace camp – Israelis and Palestinians alike – have come to terms out of weariness and fatalism… it is not the Jewish or Zionist identity that I fear for, but something more important: our humanity and the humanity of the Palestinians in our midst. We are not Americans in Vietnam, the French in Algeria, or the Soviets in Afghanistan, who one day get up and leave. We will live with the Palestinians for eternity, and every wound and bruise in relations between the two peoples will be engraved in the memory and passed on from one generation to the next. Accordingly, we must try to examine the situation with intellectual honesty and think about other solutions that can stop this process and reverse it. What’s in danger now is not Israel’s Jewish and Zionist identity but its humanity – and the humanity of the Palestinians who are under our rule.”

It is this danger that I see as motivating me to actively speak out, to place what pressure I can on Israel to recognize the error of its ways. It leads me to conclude that Israel is today an apartheid state and that the non-violent tactics that we used to challenge South Africa are called for in fighting the oppression of the Palestinian people.

Yehoshua and I may still be a part of what it means to be a whole Jew but we agree that it is not to be found in today’s Israel.

Haaretz column Gideon Levy captured the pain in his eulogy for a great writer. “He declared a divorce. The plan to stop apartheid: The time had come to say goodbye to the two-state vision. The unavoidable conclusions he left to those who come after him. He was no longer strong enough to move to the next phase, the unavoidable separation from Zionism. If the time of separation from the two-state vision had come, there also had to be a separation from either the Jewish or the democratic state. It’s impossible to have both. What did Yehoshua choose? … The man who had devoted his intellectual prowess to the question of Jewish identity, who reminded us of all that the Jewish people had not imagined immigrating here for the centuries during which it could have, and preferred longing and lamentations, found something more important than Jewish and Zionist identity: humanity. Goodbye, dear friend, and thank you for all the conversations.”

This article opened my eyes, I can feel your mood, your thoughts, it seems very wonderful. I hope to see more articles like this. thanks for sharing.