Marty Levine

September 4, 2021

This may be an uplifting tale of good people trying to do good things in their desire to address the nation’s growing wealth gap and its underbelly, the theft of wealth from black, brown, and indigenous peoples throughout our nation’s history. Or it may be a darker tale about privileged people using their good works to avoid confronting the need for more difficult choices and the need for reparations that might affect their own privileged status.

Or it may be both.

In my inbox a few weeks ago appeared an invite that piqued my interest A representative of the Lobeck Taylor Family Foundation (LTFF) offered me a chance to interview the Foundation’s CEO and President, Elizabeth Frame Ellison. They were interested in spotlighting the Foundations’ work, emphasizing its focus on doing something to fight back against the nation’s growing wealth inequality and in building racial and gender inclusivity. They were fully committed to building, as they said in their invite, “programs for local entrepreneurs that can be replicated in other cities across the country in order to create business equality and economic success in other local cities.” And they wanted to tell their story of success.

I was intrigued.

Having written critically about philanthropy and philanthropists, about the harm done when they act without public checks and balances to decide what problems to work on and what the right answers are, this offer was of interest to me. I wondered if this was just another Foundation following the Gates model, seeing the answers to big problems through lenses distorted by their own ego and hubris? Was it one more example of noblesse oblige in action? Did they understand the need to listen to voices of their community, to allow those most affected by society’s problems to lead the search for solutions?

The LTFF was, “founded in 1997…has grown into a second-generation investment in making Tulsa an innovative, collaborative and thriving city.”

The Foundation’s founders, Kathy L. Taylor and William E. “Bill” Lobeck, Jr., have played a leadership role in their city and state’s economic and political history. The University of Tulsa, who has benefited from their generosity, described them as having “distinguished themselves individually and jointly in public life. Ms. Taylor served a dynamic term as the 38th mayor of the City of Tulsa (2006-09) and as Oklahoma Secretary of Commerce and Tourism (2003-06) in the administration of Governor Brad Henry, for whom she also served as a key educational advisor. Mr. Lobeck achieved high distinction in the auto rental industry through a series of executive appointments…Kathy Taylor and Bill Lobeck also have sustained an exemplary legacy of philanthropy…and have long worked to advance the Tulsa community through strategically directed giving…”

According to a 2018 Interview with the Foundations COO Meredith Peeples, with new leadership came change. “For the first 15 years of its existence, LTFF primarily made grants to education, the arts and community capital campaigns….the Lobeck Taylor Family Foundation commissioned a gap analysis on Tulsa’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. The study uncovered a blueprint of what existed and created pathways for Lobeck Taylor to be a convener and grantmaker for the city. ‘We shifted the mission and focus, and our heartbeat today is innovation and entrepreneurship,’ Meredith says.

LTFF found its mission, “empowering Tulsans to achieve their goals by decreasing the barriers associated with big ideas.” It had its big problem, and it had its solution. As Meredith Peebles described in a blog post, “programs that increase and support small business ownership are certainly a critical component to the solution…can be transformational on their impacts to economic mobility and opportunity when they are able to pair both an existing skillset in and passion for an industry with resources, mentorship and access to capital…”

Rooted and devoted to Tulsa makes LTFF an interesting case example to ponder upon. 100 years after the Tulsa Massacre and the destruction of “Black Wall Street” the city is a grim reminder of the systemic nature of wealth inequity and the reality that it is the direct result of the efforts of the city’s white leadership to destroy Black wealth, power, and community.

In a recently released study, “The Color of Wealth: The Destruction of Greenwood and Tulsa’s Legacy of Loss (Advance Executive Summary), Ofronama Biu, Grieve Chelwa, Christopher Famighetti, Kate Richey, Damario Solomon-Simmons, and Darrick Hamilton paint a striking picture of the great and not yet remedied harm of our past actions. “This brutal and inhumane attack was not an isolated event. Over the following days, weeks, years, and even decades, many of the same perpetrators took actions to ensure the permanent erasure of Greenwood and the wholesale seizure of its former residents’ assets. The economic ruin of Greenwood robbed Black Tulsans of their rightful inheritance and denied successive generations the wealth, financial security, and tangible and intellectual property that might otherwise have sustained, enabled, and enriched the quality of life of an entire community. White Tulsans and local government officials began an obstructionist campaign against rebuilding Greenwood virtually immediately. The interference with rebuilding and investment in Greenwood and North Tulsa that began after the Massacre has never relented and is ongoing. There is still no viable public infrastructure in these communities. In every major category that undergirds individuals and households in their wealth-building endeavors over a lifetime (employment and educational opportunities, the availability of safe and affordable housing, a healthy environment and access to primary healthcare, etc.), Black Tulsans face shocking disparities compared to their White counterparts. These disparities are fueled by racist underfunding of public structures and deliberate and ongoing structural violence enacted by government entities whose choices impoverish the chances of Greenwood’s descendants into 2021. Meanwhile, White Tulsans enjoy these resources in abundance, provided by the very same public structures and government entities that have inflicted a shameful legacy of intentional deprivation onto Tulsa’s Black citizenry. While the exact date and time of the beginning of the destruction of historic Greenwood is well-established, we have no timestamp for when moral and economic violence of the Massacre will end. Wealth once stolen is made permanently elusive by deliberate public policy choices. A hundred years of investments in White communities and neglect and expropriation from Black ones maintain an apartheid metropolis of dichotomous “development” in the City of Tulsa.”

Recently, writing for The Institute for New Economic Studies, Lynn Parramore summarized the stark economic legacy of our nation’s racist root: “as of 2014, Black households in the metropolitan area of Tulsa had a median household wealth of only $8,000. White households, in contrast, boasted a median total of $145,000. When it came to homeownership, Black Americans came out last of all the groups studied. Only 40% of Black households owned their homes compared to 85% of White households. And even though Black households showed the lowest rate of homeownership, they had the highest amount of debt — 75% carried a mortgage. As for liquid assets, the kind that can get you through emergencies, Black households in Tulsa had a median number of exactly zero — less than any other group. White households, on the other hand, had a median liquid asset number of $12,000. Cherokee households were not far behind at $10,000. What about stocks, another key component of wealth? Again, Black households were far behind. Just 5% owned this type of wealth, compared to 37% of White households. The only group with a lower rate of stock ownership than Black households was Mexican households, at 3%. Black households also had the highest rate of student loans and the second-highest rate of payday loans – the type of debt most poisonous to economic wellbeing.”

In a recent Newsone article authored by Ms. Ellinson and Shakori Fletcher, the Partnerships Director for the Limited Time Only Market at the Shops at Mother Road, (an LTFF supported venture) the Foundation’s intent use entrepreneurship to take this legacy on directly was made quite clear. “When the Lobeck Taylor Family Foundation laid the groundwork to build Tulsa’s entrepreneurial ecosystem during the Great Recession in 2009, we imagined a world where entrepreneurship was accessible to all. Black Tulsans are more than twice as likely as their white counterparts to be unemployed and continually face significant disparities in educational attainment, food security, wages, unemployment, imprisonment, and police brutality… We worked with our community to create a pipeline to entrepreneurial success for ANY Tulsan with the hustle and passion to pursue their goal.”

The Foundation has operationalized its vision by creating several programmatic ventures including 36 Degrees North, “Tulsa’s Basecamp for Entrepreneurs, where the private and public sector meet to support and connect Tulsa most driven individuals.” They have also created the Mother Road Market, Kitchen 66, and The Shops at Mother Road Market to provide budding entrepreneurs “the opportunity to use a small shop model to test and scale their latest concept without the financial risk of opening a full-scale brick-and-mortar business, access to affordable brick-and-mortar retail locations, marketing and communications support, business training programs, and sales & distribution opportunities…”

In 2020 their focus became even sharper, “focusing specifically on equitably activating one corridor in the community” and achieving “outcomes related to Placemaking along Route 66 that fall into three primary categories: Pride of Place and Community Attachment, Physical Infrastructure and Economic Activity and Equity. We believe this focus will help us better assess impact of the dollars we spend to fulfill our mission…” The area they would concentrate on was one where “nearly 20% of residents live at 50% BELOW the poverty line with a $16,764 median household income compared to $51,623 in Tulsa MSA”

These are good works. They have an important outcome in mind. But are confronting the real problem? And are they addressing the reality of the wealth gap?

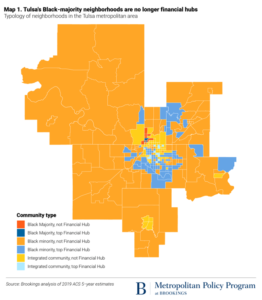

The financial segregation of modern Tulsa was illustrated in this chart developed by Andre M. Perry, Anthony Barr, and Carl Romer writing for Brookings earlier this year:

The authors focused on the value of the real estate lost in 2021 as $200 million in current dollars. This does not include the lost wealth from businesses that could not generate profits year by year and the lost wages of their employees. It does not include the value of the broader economic cost of our nation’s racist housing policies. Nor does include any valuing of the wealth stolen from enslaved people, before and after the emancipation.

This is the historic challenge faced by the city that the LTFF is so deeply committed to. The problems that they have for the past years focused their efforts on ameliorating are direct results of this history. This Foundation and its leaders know that change is needed. They are aggressively using their resources to focus on a long-term effort to build, one by one, a new generation of small business owners who can jump over the wealth gap by developing their own wealth. The Foundation is using its best efforts to model a form of urban renewal so that it can be replicated widely across Tulsa and beyond.

What they are not doing is directly addressing the “centuries of unjust public policies, from slavery to segregation to redlining, allowed white households to accumulate wealth through opportunities that were systematically denied to (and frequently came at the expense of) people of color. The outcomes of past injustice are carried forward as wealth is handed down across generations and are reinforced by ostensibly “color-blind” practices and policies in effect today.”

In the end, the LTFF is just one more example of good, privileged people trying to solve our most difficult societal problem without impacting their own status, wealth, and comfort. The Foundation may be building a next generation of business success that may work for a small but growing cadre of new business owners. They are revitalizing one area of Tulsa that sorely needs new investment. They may have an approach that can be replicated and scaled.

It is not directly addressing the outstanding IOUs that the beneficiaries of the centuries of government-sanctioned theft have left unpaid. Is it up to those who have benefited most from this historic crime to decide when and how their reparations should be made? Can the deep problems that remain in our nation be solvable without addressing the redistribution of wealth and power directly?

Last May, almost 100 years after the massacre, Tulsa City Councilperson Kara Joy McKee, in supporting an effort to finally address the need for reparations for the harm done, recognized that “it is really important that the community tells us what ‘making amends’ would mean to them. And so, this resolution will initiate a process by which we will go out into the community, meet folks where they are, and ask them what making amends would mean here.”

Is it not time for the philanthropic community to step forward and put their weight behind the effort to enact law and policy that brings structural change at the local, state, and federal levels? And is it not time for them to commit their resources to following the impacted community’s direction on how they want the debts they are owed to be repaid?

These are the nagging questions that plague modern philanthropy. Philanthropists and their Foundations say they want to do the right thing. They say that they want to make the world a better place. But they also want to remain in control of the process. They want to remain in control of where and how risks are taken and of whose lives are put at risk. To ask them to put their own comfort on the line, to put their own power and wealth on the line, maybe too much to ask.

But is it really taking on the root causes of wealth inequality?

And this is where we come back to the beginning of this story, an email in my in-box pitching a story.

That interview happened and then it was gone, but that is another story.

1 Response

[…] this month I wrote about the complicated nature of modern philanthropy. How good intentions may not be enough to […]