Marty Levine

February 25, 2022

How important is understanding our history? Is it important for us to open up the wrongs of the past as we try to understand our current reality? Is it important to know why our country is as it is even when those facts make us uncomfortable?

As you think about these questions, consider the findings of a study, “Housing Divide”, recently published by ABC News and FiveThirtyEight. They looked at residential patterns in cities across the country. They found that in many of our cities that communities think are diverse; rather, looking at their data, it seems segregated would be an accurate way to describe their residential patterns and most residential patterns in the US in 2022.

It is comfortable to think that housing patterns reflect individual decisions about who individuals want their neighbors to be. This would mean that Black Americans are more comfortable living in predominantly Black neighborhoods, often neighborhoods that have been underinvested in by public and private resources. This is one way to avoid dealing with the problems before us — to blame individuals for their own struggles and to absolve those who caused the current reality and are its beneficiaries.

Black Americans and other communities of color have been kept in their own, contained communities in cities and towns, north and south. But it was an agency of the Federal Government, The Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), that created the mechanism for maintaining these housing patterns and prevented Black Americans from benefitting from the economic revival following the Great Depression and the booming years following World War II.

The HOLC, a New Deal program, was designed with a noble purpose, to help homeowners avoid defaulting on their mortgages and losing their homes. With its resources, it refinanced and assisted more than 1 million home mortgages, allowing homeowners to remain in their homes and protecting the banks who had made those loans as well.

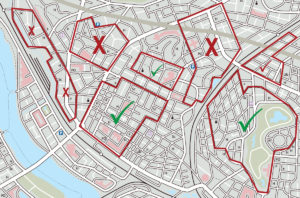

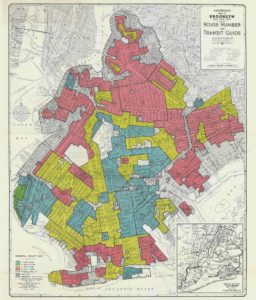

In 1939 the HOLC took an action that was designed to ensure that it used its money well and began to classify the loan-worthiness of residential neighborhoods, beginning in Cleveland, Ohio. From this effort emerged a set of maps that designated some areas a safe for investment and others as too risky for a prudent investment.. The critical factor in their assessment was the racial makeup of a community and of the home buyer. According to the Federal Government, being Black and living in a Black neighborhood made one unworthy of a home loan.

As Housing Divide tells us, HOLC mappers modeled their approach in Cleveland and “one of the neighborhoods that officials visited — now known mostly as Fairfax — was 55 percent Black, and as such, they gave this area a “D” grade, meaning they thought Fairfax was “hazardous,” or at high risk for defaulting on mortgage loans. In their report, HOLC officials concluded that property prices were trending down due to a “strong colored infiltration” and that there was a “detrimental change of ownership occupancy from white to colored.” Fairfax, like most metropolitan neighborhoods where Black people lived in the early 1900s, was then marked with red ink in the HOLC’s maps — a practice referred to as redlining.”

The HOLC, an agency within our national government, created the tool for residential Red Lining and embodied the way that public policy reflected the bias of large segments of White America. This bias framed their work in city after city. And it became the way public and private mortgage-makers and real-estate professionals approached their work.

The timing of this is important. Federally authorized maps were there for public and private mortgage makers as the Great Depression ended, as World War II was fought and won, and as millions of GI’s returned to our shores. Those maps were in place to control how the housing benefits provided by the GI Bill allowed millions of veterans to become home buyers. The maps and practices that were the product of the HOLC determined what homes could be purchased based on the race of the buyer. Families’ ability to grow their wealth based on rising home values was also determined by where a purchase could be made. Thus, not only were residential patterns buttressed, so were patterns of racial, inequitable financial security.

In 1968, as the Civil Rights Movement pushed to break down our nation’s racial barriers, Congress passed what became known as the Fair Housing Act. With a stroke of President Lyndon Johnson’s pen In it became illegal to discriminate when selling, renting or financing housing based on race, religion, national origin, and sex.

Just making it illegal did not do away with the harm that has been done nor did it cure the hearts and minds of those who wanted these policies in the first place. Housing Divided’s research found that “formerly redlined zones in the Northeast and Midwest are among the most segregated areas in the country. In those regions, a higher proportion of Black Americans live in redlined zones compared with those zones’ surrounding areas — and a higher proportion than can be found in other regions of the country. “

Bruce Mitchell, a senior analyst at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition explained to the study’s authors the lingering impact of HOLC’s work. “[Redlining] biased where investment was made…with “hazardous” areas…suffering from years of neglect…this lack of investment in formerly redlined areas that is one of redlining’s most devastating consequences.”

The patterns of underinvestment, of redlining, continues. “Last year, a team of researchers released a report that looked at bank lending data and public investment documents in Pittsburgh from 2007 to 2019, finding that just 7 percent of home mortgage loans went to predominantly minority neighborhoods in that time period, despite the residents of these neighborhoods comprising almost 21 percent of the city’s population. And out of $11.8 billion in loans to borrowers, less than 4 percent went to Black people.”

According to Andre Perry, a senior fellow at Brookings Metro and author of “Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities, “Redlining happened. It was an important part of American history. And we must reckon with the behaviors and the outcomes in ways that never discount what redlining did. And again, it has different stories for different cities, but redlining is a part of that story. It just is.”

Dig deeper into our history of protecting segregated housing and you will find even more that may make you uncomfortable. Here’s how Richard Rothstein, author of “The Color of Law, described a wider perspective: “The refusal of federal agencies to issue mortgages to those neighborhoods in the 1930s and 40s — that’s one of many policies that were followed…For instance, even though it is one of the most segregated cities in the country, Detroit’s segregation doesn’t match up with its formerly redlined zones. This is in large part because as Black southerners moved into Detroit during the Great Migration, white Detroiters responded by leaving the city in droves, mostly moving out to federally subsidized and racially homogenous suburbs — a migration that historians call “white flight.” White Detroiters went through great lengths to keep their wealthy suburbs exclusively white, too, with measures as extreme as building a half-mile-long concrete wall to physically separate themselves from Black families.”

The Authors of Housing Divide captured the continuing reality of actions taken more than 80 years ago. “The legacy of redlining extends far beyond housing segregation, too. Its impact can be seen today in minority neighborhoods’ access to health care, poorer educational opportunities, and increased risk of climate change, as many of these areas are more prone to flooding and extreme heat. Without a serious confrontation of its lasting generational damage, the racial segregation caused by redlining isn’t going anywhere either.”

For White America, this is not a pretty story. Whether I as a white-identifying person, was alive in 1939 or not, whether I was then able to buy a home that allowed me to increase my wealth or not, I still benefitted from this disgraced set of public policies. If I will not, if we not as a nation take note of this history and take responsibility for iyt, we cannot undo the harm done, done by others perhaps, but to my benefit. That is the uncomfortable soul-searching that we see being fought against so hard in the loud voices before school Boards and in legislative chambers.

James Baldwin, writing A Letter to My Nephew in 1962, put this more eloquently. Describing the reality of a world controlled by White America for our own burden he concluded that these historic harms are things we “do not know…and do not want to know…but it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.”

Personally, I know I need to keep pushing back on this effort to ignore our history and to avoid taking responsibility for these harms. I hope you are with me and we can push those who cannot, will not, face these uncomfortable truths. We must not erase them from our history.